Kaiser’s company was one of those that built the Hoover Dam, but he knew practically nothing about shipbuilding. However, rather than seeing this as a disadvantage, he approached the challenge from a fresh perspective. Instead of relying on British expertise, he asked himself how to build ships without expert workers. His solution was to redesign the assembly process using prefabricated parts, so workers only needed to learn a small part of the job. He introduced American assembly-line techniques and, unaware that heavy machinery was supposedly necessary for cutting metal accurately, had his workers use simple oxyacetylene torches instead. Similarly, he replaced traditional riveting with welding, which proved both cheaper and faster.

History

Japan drives on the left side of the road due to a historical tradition stemming from the Edo period (1603-1867) when samurai, who wore their swords on their left hips, kept to the left to avoid accidental clashes and potential duels.

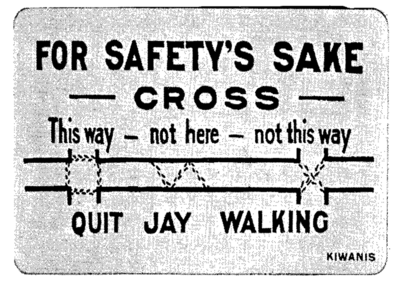

The term “jaywalking,” referring to crossing the street recklessly or illegally, was coined by the US auto industry to shift blame for car accidents from drivers to pedestrians.

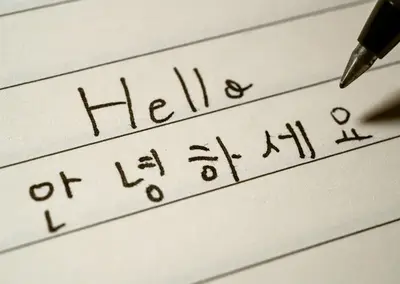

As crazy as it sounds, the Korean language was invented by one man’s kindness. In the 1400s, many lower class Koreans were illiterate due to the complexity of their language Hanja (effectively literary Chinese). So to promote literacy among the masses, the fourth king of the Joseon dynasty, Sejong the Great, personally created and promulgated a new alphabet known as Hangul, which has remained in place ever since.

What’s the best way to recruit British soliders in World War I? Appeal to authority. The iconic poster used none other than Lord Kitchener, the British Secretary of State for War, to motivate the public to volunteer.

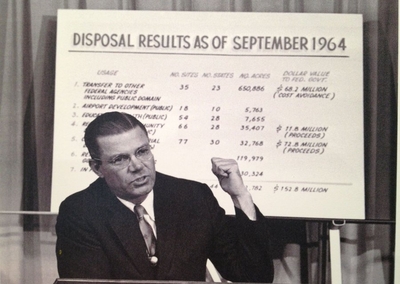

The McNamara fallacy – making a decision based solely on quantitative observations and ignoring all others – is named after Robert McNamara, US Secretary of Defense during the Vietnam war. He measured success solely by tracking body count, which, although quantifiable, ignored crucial factors the enemy’s guerilla tactics and the loyalty of its soldiers.

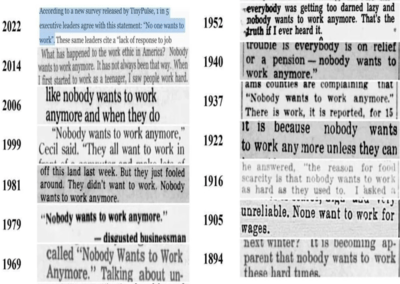

It’s a tale as old as time.

Obesity is now considered a medical illness, but this is a modern phenomenon. Throughout history, obesity was seen as a sign of wealth and high socioeconomic status – when food was scarce and famine was rife, only the most prosperous could afford to indulge. The art of Renoir and Rubens presents an ideal figure that is very different from the one today.

Advertising was banned on the Thames in the 1920s, so gravy manufacturer Oxo decided to build their logo into the windows at the top of their tower. It’s now one of London’s most iconic buildings.

Thomas J. Barratt understood media principles long before they were in textbooks. In the 1860s it was illegal to tamper with British coinage, but French centimes were still legal tender in Britain. So he imported 250,000 centimes, engraved them with ‘Pears’ soap’ – the brand he managed – and put them into circulation.

Pineapples were once the ultimate symbol of wealth; used mainly for display at dinner parties, rather than being eaten. Charles II was so taken with pineapples that he commissioned a portrait of himself being presented with one. But they lost their star status once steamships started to import them to Britain from the colonies, and they became afforable to the masses.

Wedding dresses are synonymous with white, but we only have Queen Victoria to thank for this. For her marriage to Prince Albert in 1840, she decided to buck the trend of wearing red (white was reserved for courtrooms), and popularised a trend that has remained ever since.

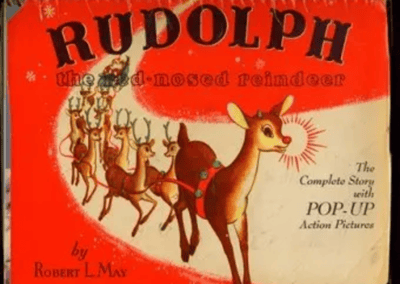

Christmas might be the most magical time of year but it’s still motivated by profit: Rudolph the Reindeer was originally a promotional tool. Retailer Montgomery Ward had been buying and giving away booklets for Christmas every year and decided that creating their own book would save money. So in 1939 copywriter Robert L. May created Rudolph as part of the first published book, eventually selling 2 million copies.

Tanning vs pale